JCSU’s Massive Photo Collection of Black Charlotte History

James Peeler's photography shines a light on a half-century of history

When Latrelle Peeler MCAllister was a young child, she would accompany her father to his studio, a modest storefront he leased at 1404 Beatties Ford Road. Only years later did she understand the personal and historical significance of the hours he spent there.

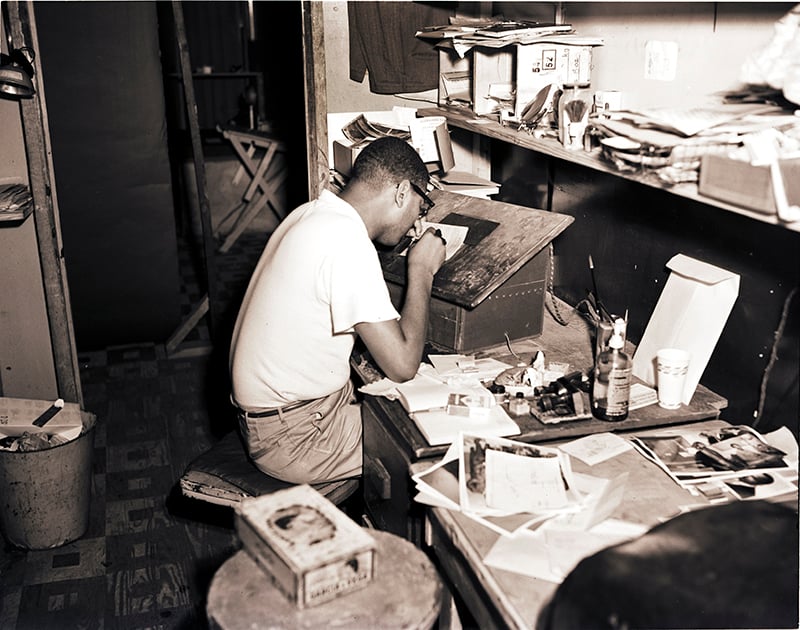

“When I was probably 4 or 5, he would put me on top of a metal trash can in the darkroom and try to teach me about how to use light to develop pictures,” says McAllister, now 66. “He would allow me to dry pictures on a drum dryer. I observed him retouching photographs. He did that by hand—and I’ll tell you, he would have given Photoshop a run for its money, because he was really gifted in that area.”

James Peeler was a professional photographer, a Korean War veteran who had studied at the New York Institute of Photography on the GI Bill. From the mid-1950s until his death at 74 in 2004, he took tens of thousands of photos. They were mostly family portraits, along with shots of weddings, funerals, graduations, and other signposts of life in the city’s Black community. But he photographed scenes of ordinary life, too: families outside their homes, young men playing volleyball, couples dancing at the original McCrorey YMCA on South Caldwell Street in the Brooklyn community. He took photos of the day’s local and national Black luminaries, too, including Thurgood Marshall and, more than once, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

Peeler kept them on shelves, in envelopes alphabetized by his clients’ names, in a 12-by-12-foot shed behind the family’s home at 2421 Lasalle St. in the University Park neighborhood. The collection of negatives and prints grew and grew—to 100,000 images, then 150,000, then more. In October 2003, as his health was failing, the kerosene lantern Peeler used to heat his at-home workshop started a fire. He and his wife, Ida, survived without serious injury. But the house was damaged—later razed and rebuilt—and the Peelers had to find a new home for the pictures.

It so happened that their daughter worked in administration at Johnson C. Smith University, a five-minute drive away, where Peeler had earned a degree in 1951. McAllister at first arranged for the Levine Museum of the New South to store her father’s archive, which filled 37 Rubbermaid tote containers. Then she considered donating it to UNC Chapel Hill, her own alma mater. But she ultimately chose JCSU’s James B. Duke Memorial Library, which accepted the photos in 2010.

Then came another challenge: sorting through all of it. “I don’t think he thought real carefully about how to preserve the work,” McAllister says. “So some of them were in worse shape than others. But, amazingly, they survived.” The task fell to Brandon Lunsford, the university archivist. He needed help—and got it from a $100,000 grant from the State Library of North Carolina. That allowed Lunsford to hire a fellow archivist, Chelly Tavss, to organize about 50,000 and digitally scan about 3,000 of an estimated 200,000 images. Identifying people and long-demolished buildings was a challenge, too, as Peeler left only sporadic information about what he shot.

Tavss left for another job after a few years. But the public can see the results of her work—the James G. Peeler Collection, a half-century of Black Charlotte life captured for posterity by one man—via the James Duke Library’s DigitalSmith online archive.

Most of the images remain in their envelopes. After Tavss’ departure a decade ago, Lunsford did what he could, either by himself or with the help of student volunteers. But especially after COVID, he says, the demands of his archivist’s job grew too great, and he left JCSU in September. Lunsford now works as a freelance historian and archivist.

McAllister has departed JCSU, too, having retired in 2023. She recognizes the collection’s value as a historical record, of course, but that walks hand in hand with the personal. “One of the things about the photographs is that you can see the humanity in people. You can see the emotions in people,” she says. “I hope that, as time progresses, people who were not a part of that time will be able to see the humanity and emotion of the people who paved the way for them—that they’ll understand what it took to get us to where we are now—and they’ll have a sense of what their responsibility is as they pick up the mantle and help to move the nation forward.”

At Home

Even in a segregated society, Black Charlotteans built lives for themselves and their families, as Peeler himself did. In the 1950s and ’60s, families settled in new communities outside the city center—like Northwood Estates, off Beatties Ford Road in what’s often called the Northwest Corridor.

Worship

Churches have served as the backbone of Charlotte’s Black community since 1864, when missionaries organized Clinton Chapel AME Zion Church near South Mint and Stonewall streets. By 1896, Black churches outnumbered their white counterparts. Urban renewal projects, especially the effort that demolished and displaced the Brooklyn community in Second Ward, closed and scattered many of the churches that had formed the social hubs of Black Charlotte. Peeler’s images chronicle the days of a faith community just a few years before its forced transformation.

Little Rock A.M.E. Zion Church, on North Myers Street, was one of the most prominent Black churches in the city

Weddings and Funerals

They were, and remain, red-letter days in community life. “The thing that struck me odd as a child was a lot of funerals and just pictures of bodies,” McAllister says. “Because, in the Black community, there was this thing, ‘Oh, they put that person away really nicely.’ It was a sense of pride about family members having elaborate funerals.”

Daily Life

McAllister refers to Exposures of a Movement, a 1996 documentary by the late Steve Crump about her father and other prominent Black photographers in the 1960s. “That really helped contextualize things for me,” she says. “One of the people who was interviewed was Charlotte attorney (J.) Charles Jones, who was also an alum of Johnson C. Smith, and he was one of the students on the front line in the Charlotte Civil Rights Movement. He talked about the students making a conscious effort to call my father because they knew if he was there with his camera that they would have a measure of protection. It was then that I began to understand that by recording history in this manner, the Black photographers of the day actually paved the way to changing some of the laws and restrictions throughout the country, because they personalized the people who were protesting.” Jones died at 82 in 2020.

Charlotte has its own chapter of the Civil Rights Movement. Peeler captured protestors outside the Dowd YMCA (above) and at a police station (below).

Around Town

As a teenager, McAllister was impressed when she learned her father had shot album covers for R&B bands like Maurice Williams and the Zodiacs and The Soul Patrol. They were among the “Chitlin’ Circuit” acts that played venues like the legendary Excelsior Club on Beatties Ford. But her biggest thrill had come years before. “I think I was 5, and he was taking pictures of the Thanksgiving Day parade. He would often carry me when I got tired, you know, put me on his shoulders. We’d been there throughout the parade, and at the end of the parade, the guy—Santa Claus—said, “Hi, Mr. Peeler.’ And I was so impressed as a 5-year-old. I said, ‘Daddy, you know Santa Claus!’”

The original McCrorey YMCA, at 334 S. Caldwell St. (above), was another social hub in the ’50s and ’60s, along with the Excelsior Club (below) on Beatties Ford Road.

Notable People

“You know, the world saw Black society as one thing, but we saw it in a completely different light,” McAllister says. “Through his work, we’re able now to have images of Black doctors and lawyers in our neighborhood, University Park. We had Fred Alexander, the state senator; Kelly Alexander (Sr.), the civil rights activist and funeral home owner. We had teachers. We had bankers. He was able to show the world the strides that the Black community had made.”