A Plea To Revisit An American Classic

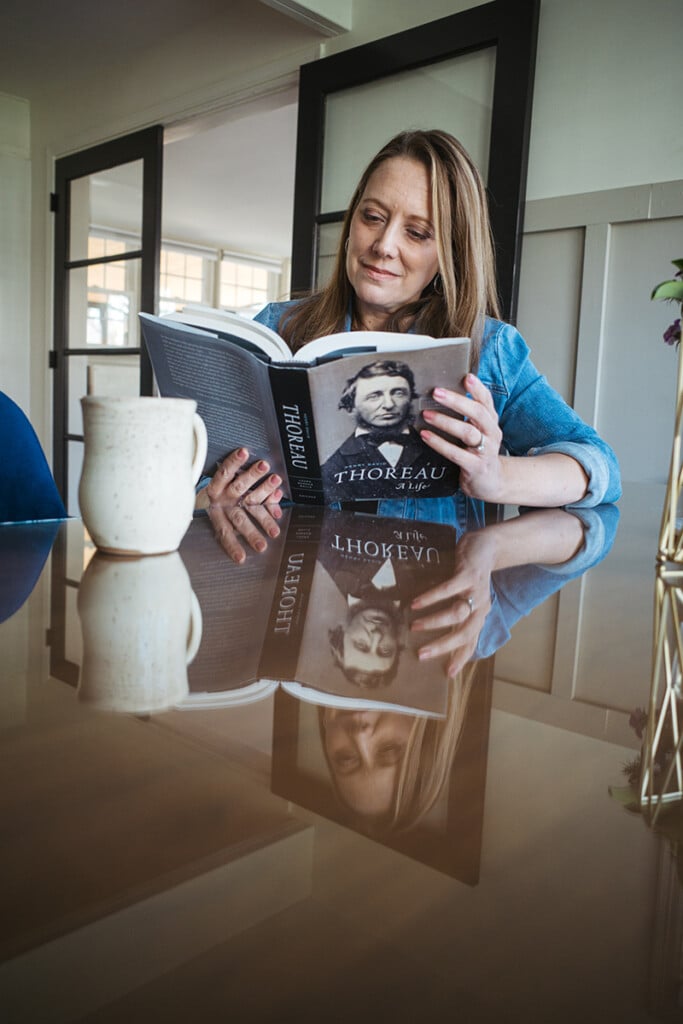

Jen Tota McGivney reexamines Thoreau in her new book, Finding Your Walden

Books are best read at the right moment, and rarely is a high school English class the right moment to read Walden. Revisit Henry David Thoreau’s book as an adult, however, and some lines—“The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation”—hit harder.

When I studied Thoreau in graduate school at Winthrop University, I was his age at Walden Pond: 30. We shared preoccupations with questions of career, success, and time well spent—how to make a good living while living a good life. Walden isn’t just beautiful literature but a manual to overcome distractions, resist conformity, and live fully. Those skills have become superpowers today.

Thoreau embraced a pragmatic idealism as the U.S. reeled politically, socially, and economically. He worked gigs as a surveyor and tutor to fund low-paying writing work and support his parents. He was an Underground Railroad operative, even after the Fugitive Slave Act threatened to imprison or bankrupt him. He threw a party each year for everyone in town but reserved moments of solitude each day. Thoreau lived a life of meaning, contribution, and connection while paying the bills. The dream.

Parallels between Thoreau’s time and ours have grown unfortunately similar (politics, technology, and pandemic, oh my). Distractions and isolation plague us. Injustices require action. In Finding Your Walden, I turn Thoreau’s ideas into a five-part philosophy of living well, even now—especially now. In this precedented time, Thoreau’s ideas are just the company we need.

Excerpt from Finding Your Walden: How to Strive Less, Simplify More, and Embrace What Matters Most

(Walden) is a document of increasing pertinence; each year it seems to gain a little headway, as the world loses ground.

—E.B. White

History may not repeat, but it often rhymes, or so Mark Twain (might have) said. Our times rhyme with the times of Henry David Thoreau as neatly as a Dr. Seuss story.

If we could span a 175-year divide to pull up a chair beside Thoreau, we could chat all day with him. We’d talk about the pros and cons of belonging to generations when technology advanced more in our lifetimes than during previous centuries, revolutionizing how people lived, worked, and communicated. We’d gripe about dirty partisan politics, fanned by companies profiting from the divide. We’d talk about the rich getting richer, and the rest of us just working harder. We could even discuss how living during a pandemic compelled us to question our priorities and our relationship to work.

And yet! And yet “In these unprecedented times . . .” has become a cliché in news, in ads, in conversations. Why do we feel so alone in history? I believe it’s beyond coincidence that our loss of historical connection has happened as fewer people read classic literature. These books didn’t become classics just by getting old. They did because they’re timeless stories about how people got through the chaos of life and how we might, too. These stories can give us company during these very precedented times. And we can find plenty of company in Thoreau’s 1854 masterpiece, Walden; Or, Life in the Woods. In it, Thoreau looks at his fast-changing, conflict-ridden, overpriced world and wonders: Do I really need all this stuff? When should I take a job—and when should I leave one? What’s my duty as an ethical citizen of a less-than-ethical world? How can I live a good life amid (insert hand-sweeping gesture) all of this?

We get it. We live during a similar philosophical reckoning. We now question assumptions that we barely noticed we even had—about what we need, what we don’t—and we search for a new way, a simpler way. Thoreau’s writing points us toward this way. He’s proof that we’re not as isolated as we feel, that another generation navigated something like this already and left guidebooks behind to help.

It’s not just our generation that resists reading old books, however. Thoreau lamented that, even during his lifetime, not enough people hit the classics for inspiration. In Walden, Thoreau made a solid case to seek insight within the bindings of old books:

How many a man has dated a new era in his life from the reading of a book. The book exists for us perchance which will explain our miracles and reveal new ones. These same questions that disturb and puzzle and confound us have in their turn occurred to all the wise men . . . and each has answered them, according to his ability, by his words and his life.

No book has dated a new era in my life like Walden has. No author has answered the questions that disturb and puzzle and confound me like Thoreau has. I’ve toted my dog-eared, underlined Everyman’s edition with me for decades like a talisman. Walden has changed my life, and I’ll show you how it might change yours, too.

Not Just Less Stuff, Better Stuff

When people distill Walden down to a tattoo or bumper sticker, it’s usually his most famous line: “Simplify, simplify.” But it’s easy to miss what Thoreau simplified for. He didn’t simplify to have and to do less; he simplified to have and to do more of what mattered. To trade up, he pared down.

Contrast that to life today. We’re drowning in a culture of accumulation. We never quite earn enough. Have enough. Do enough. We never quite are enough. We focus on what’s next, believing that when we earn/have/do/become a little more, we can finally relax. We don’t, of course, because then there’s more to earn/have/do/become. There’s a term for this: lifestyle creep. In its advanced stages, we bury so much of that good stuff we started with—our curiosity, our joy, our us-ness—beneath the weight of expectations of the person we hope to become without realizing the value of the person we’ve been all along.

When we live in an era that moves so quickly, it’s hard to pause long enough to wonder if we prioritize the right things, pursue the right goals. This is by design. The lifestyle that we’ve been sold lines others’ pockets more than it enriches the quality of our days. We’re told that work should be our passion, which makes overtime feel more like a sacrament than a sacrifice. Social media transforms our time—our life!—into engagements to be monetized. Consumerism makes everything available for purchase: status, beauty, health, even youth. New devices are sold to streamline our lives, but they distract us from them. “Our inventions are wont to be pretty toys, which distract our attention from serious things,” Thoreau wrote.

As a transcendentalist, Thoreau believed that people are innately good and that we are born with an intuition that will guide us to the right decisions if we listen to it. It’s our job not to drown our intuition beneath the demands of a society that doesn’t have our best interests at heart. “I am convinced, both by faith and experience, that to maintain one’s self on this earth is not a hardship but a pastime, if we live simply and wisely,” he wrote.

It’s a crucial time to seek wisdom in this philosophy. “A cardiologist, endocrinologist, obesity specialist, health economist and social epidemiologists all said versions of the same thing: Striving to get ahead in an unequal society contributes to people in the United States aging quicker, becoming sicker and dying younger,” according to a story in The Washington Post. While many of these strivers have no choice (people who work multiple jobs to put enough food on the table), others do so voluntarily. It’s what we’re conditioned to do—to never stop climbing—as success perpetually awaits on the next rung. But this isn’t the only version of success. It’s worthwhile to question what this society asks of us and what we’re willing to give it. And no writer questions that better than Thoreau.

Thoreau encourages us to define success for ourselves—to recognize when we can strive a little less and live a little more. He teaches that there can be more power in letting go than adding on.

This is a message of radical hope. Thoreau insists that life has so much joy to offer if we live intentionally and prioritize wisely. How we choose to live can become our greatest art:

I know of no more encouraging fact than the unquestionable ability of man to elevate his life by a conscious endeavor. It is something to be able to paint a particular picture, or to carve a statue, and so to make a few objects beautiful; but it is far more glorious to carve and paint the very atmosphere and medium through which we look, which morally we can do. To affect the quality of the day, that is the highest of arts.

Thoreau had one mission: to encourage people to pause, to notice, to question. He points to the beauty of what’s in front of us, if only we’d see it: “Heaven is under our feet as well as over our heads.” To do that, we must consider if a better way of living exists, even if it’s one that no one has thought of yet—or, perhaps, especially if it’s one that no one has thought of yet.

A Tough Read and a Hard Sell

I admit that Walden isn’t an easy read. The language is dated. Thoreau’s dad jokes have aged from corny to inscrutable. (The guy loved a pun.) Suggesting that someone unwind after a hard day with 19th-century literature is a big ask. We’re inundated with words all day: emails, articles, texts—it never stops. The problem isn’t that we don’t read; it’s that we read so much that it feels hard to relax by reading even more. When we skip the great books, however, we miss so much—enjoyment and challenge, sure, but we also miss the chance to meet someone who lived centuries ago and think, “Hey, you too?”

After years of trying and failing to get my friends to read Walden (I’m fun at parties), I changed tactics. I pitched a story to Success magazine about how the messages of Walden can improve our work lives. Pitching a story about Thoreau to Success is like pitching a story about barbecue to Vegetarian Times. Thoreau’s reputation isn’t exactly about crushing it in the office. But it worked. The grateful reader emails I received proved that Thoreau is the man for our age, even if Walden might not be the reading material for our time.

I’ve expanded that concept here. I’ve turned Thoreau’s writings into a philosophy of 21st-century intentional living. In this book, you’ll learn why experts—from physicians to career coaches to psychologists—support Thoreau’s ideas as inspiration for living well. Alongside them, you’ll read about people who live those ideas today, who make big and little acts of everyday resistance against the demands of the status quo. This book isn’t a step-by-step guide to intentional living but a choose-your-own adventure. It shares all kinds of ideas, from major life-upending experiments to minor lifestyle tweaks. What does it look like to live a Thoreauvian life? For one couple in this book, it looks like selling their home to fund a year-long sabbatical in Bali with their kids to rediscover what they need (and what they don’t) and who they are (and who they aren’t). For some, it looks like downshifting to a four-day workweek or adopting a digital sabbath. For one woman, it simply looks like downsizing her clothes into a capsule wardrobe that declutters her closet and streamlines her routine. Each person has applied creativity, simplification, and joy to the experiment of life and offers inspiration on how we might too. If you take one thing from Thoreau and the people in this book, take this: Life is, after all, an experiment. No one can tell us how to do it; it’s something we need to figure out as we go. And if our life looks suspiciously like the lives of the people around us, we might be doing it wrong.

Adapted and reprinted with permission from Hampton Roads Publishing, Finding Your Walden by Jen Tota McGivney is available wherever books and e-books are sold or directly from the publisher at redwheelweiser.com or 800-423-7087.